In part 1, we described the problems we set out to solve with a lerna monorepo. Part 2 describes how we created an actual monorepo and migrated an existing codebase into it and the lessons we learned.

Spoiler: we like it, but it required some work to get to that point.

The Pilot Project

The tool most commonly used in the Javascript ecosystem to manage monorepos is Lerna, which is what we ultimately decided to move forward with.

We were a little hesitant to commit to a full-out migration without a trial period, so we decided on a mini-migration of about half a dozen components to make sure that a monorepo was the right solution.

Our goals for the pilot migration were relatively straightforward:

- Move half a dozen specific components and utils from our existing design system repo into a monorepo. Include small components, large components, components that depend on other components, and components we expect to be under active development so we can stress-test lerna.

- Make sure unit testing, screenshot testing, interaction testing, and publishing packages are in good shape, and are scalable.

- Find all repos that consume the migrated code from the legacy design system, and switch the imports to use the versions in the monorepo.

However, migrating a few components independently as individual packages is a bit more complicated than migrating a whole repository at once.

Code Organization

It’s common for the main source code of a non-monorepo repository to live in a src/ directory. Instead, Lerna encourages you to use a packages directory. Generally the packages folder is a flat listing of every package in the repo, but we found that a bit more structure was ideal. Since this was common front-end code, we decided to break everything down into four categories, with the caveat that we could add more if there was a good case:

- assets for images/icons/fonts/etc

- components for our react and javascript components

- styles for anything aesthetic

- utils as a catch-all for functions and constants we might want to be available from multiple places

This allowed us to create a structure and force developers to easily adhere to it. We found we could get lerna to follow this structure by setting the packages property in the lerna.json:

"packages": [

"packages/assets/**",

"packages/components/**",

"packages/styles/**",

"packages/utils/**",

"packages/node/**"

]This directory structure was significantly different from the organization of the code in our legacy design system, which is a small issue we had to deal with when importing components. A much more complicated issue was git history.

Migration With Git History

We weren’t willing to lose the git history of our legacy Design System library in the migration process. It was important to us that after migrating code, we could still identify the original authors and when they made changes.

The lerna import command maintains history, but it is designed for migrating an entire repository into a single package in the monorepo. We only wanted to migrate a few components for the pilot, and we wanted each component to have its own package. In order to migrate components one at a time, we wrote a shell script that took in a few command line parameters:

$PACKAGE_NAME(the name for the new package post migration)$SRC_REPO(a url that can be used to clone the old repository)$IMPORT_SUBFOLDER(the path to the code to migrate)$CATEGORY(utils, components, styles, assets, as outlined above)

The script ran in a few different steps:

- Create a fresh clone of the source repo, for us usually our design system

git clone $SRC_REPO- Filter the git history of this clone to just the desired component

git filter-repo --prune-empty always --subdirectory-filter ${IMPORT_SUBFOLDER}

git tag -d `git tag | grep -E ‘.’`- Commit a new package.json for this component with at least:

{

name: "@your-monorepo-domain/category-package-name",

version: "1.0.0"

}- Rename the clone folder to

${PACKAGE_NAME} - Use lerna to import the mutated clone:

lerna import ${PACKAGE_NAME} --dest="/monorepo/packages/${CATEGORY}/${PACKAGE_NAME}" --preserve-commit --flatten -yAt this point, all the code that began in the design system repo in /src/${PACKAGE_NAME} would have been migrated to the monorepo in /packages/${CATEGORY}/${PACKAGE_NAME}.

The approach described above imports only one folder at a time from a legacy repo into the monorepo. We initially tried git filter-branch , which can import a set of many folders at once with their git history using the --index-filter flag, but this was slow, so we switched to mostly using the --subdirectory-filter flag and ultimately the better supported git filter-repo command.

Once a component was published from the monorepo, we updated consumer references from the legacy design system package to the newly released monorepo package. To prevent users from trying to iterate on the legacy component, we went into the legacy repo, deleted the code, and replaced it with a reference to the new package. After enough time passed and all consumers were consuming the new package, we deleted this safety net reference too.

Bootstrapping

Lerna’s lerna bootstrap command installs all dependencies from each package’s package.json file and symlinks together packages that depend on each other. It also allows individual packages to specify peer dependencies.

Each of our web applications depends on third-party libraries like React, Redux, and Styled-Components. Some of these libraries require applications to rely on a singleton instance of the library at runtime, even though many front-end components may independently import from the library. To allow many components to consume a library but ensure that only one instance of the library is present in a web application at runtime, we specify the library as a peer dependency of packages that use it. We also specify a version of the library as a dev dependency in the package.json at the root of the monorepo; that version is installed to test against in the monorepo in CI and on dev machines.

We created these guidelines for specifying package dependencies:

- Is the dependency used only for testing, like Jest or Enzyme? If it is, it goes in a package’s

devDependencies. If it’s external (not written at Zocdoc), it also goes indevDependenciesof the rootpackage.json. - Otherwise, is the dependency another package in the monorepo? If yes, it should be in

dependenciesin your package’spackage.json. - Otherwise, put it in

peerDependenciesin your package’spackage.jsonanddevDependenciesin the rootpackage.json

These rules have worked well, with one major caveat. Sometimes, developers who import a package into a web application without having installed its peer dependencies are confused by failures due to the missing peer dependencies. Our guidance that external libraries should be peer dependencies makes confusion more likely, but it prevents us from installing multiple versions of the same dependencies in our consuming web apps.

Continuous Integration (CI)

A monorepo doesn’t operate solely on developers’ machines. We also needed to set up a continuous integration pipeline for it.

Useful Lerna Commands

Lerna provides many tools via CLI commands that are well documented in the project’s Github readme. We found these commands to be useful for migrating code to a new monorepo and building a CI/CD pipeline:

- lerna init: create a new lerna project within a repo

- lerna import: imports an external repository as a package

- lerna bootstrap: install dependencies and symlink between packages

- lerna ls: lists packages, with filter options

- lerna exec: run a command in all package directories

- lerna version: bump versions of packages

- lerna publish: publish a new package

We’ve already mentioned a few of these. These commands are enough to create a Lerna monorepo, import existing code, manage dependencies on external libraries and between packages, and create a CI / CD pipeline that runs automated tests and publishes releases.

Running Tests On Changed Packages

In our legacy design system, as the number of components increased so did the number of tests. We ran every test for every component whenever any change was made to any component, even though most tests were totally unrelated to most code changes. As the number of components increased, CI runtimes and the frequency of flaky CI run failures increased in parallel. We did not want a linear increase in the number of packages in the monorepo to linearly increase our CI runtime.

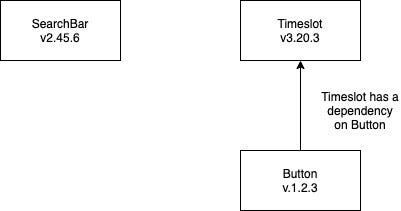

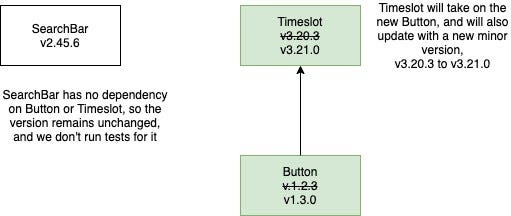

The solution seemed clear: why not just run tests pertaining to the packages where code has changed? After all, if a change is made to a Button, there’s no reason I should need to test the SearchBar, which doesn’t use it.

However, any package with a changed dependency does need to be tested, even if it doesn’t contain changed code itself. Timesgrid has Buttons, so if we change how a Button works, we need to run tests against Timesgrid using

To do that, our script can use lerna to find all affected packages:

BRANCH_POINT="$(git merge-base $(git rev-parse --abbrev-ref HEAD) $(git describe origin/master))"

changedPackages="$(npx lerna ls -p --since $BRANCH_POINT --include-dependents)"The first command identifies where the current feature branch diverged from master, and the second command uses lerna to identify all the packages affected by code changes on the feature branch since that divergence point.

Now that we know what packages should be tested, we want each of our testing frameworks to run the tests in these packages, ignoring other tests.

Unit tests

We use Jest as our test runner. In the monorepo, our Jest configuration is specified in a jest.config.js file. We use a JS config file instead of JSON to allow dynamic behavior at runtime, since we want to run a different set of tests on each commit.

Our jest.config.js

Our Jest configuration was also affected by our use of multiple libraries. Our legacy design system imported some code from libraries in other Zocdoc repositories that published separate packages. The monorepo depended on that code as well, so we configured Jest to transpile those dependencies using babel before running tests. Jest has a packages option as an alternative to roots, and in many cases, the packagespackagesrootsroots

Both Lerna and Jest can parallelize work. We invoke Jest once and let it parallelize tests instead of using lerna exec to invoke Jest multiple times. This was also to ensure that Jest transpiled each dependency only once.

Linting

Linting is the fastest step in our testing pipeline, so we took the naive approach and sequentially invoked ESLint on each affected package.

Interaction tests

For interaction tests, we use Cypress. We use a bash script to search for Cypress test files in the changed packages and then pass those into the —-spec flag in the cypress run CLI command.

Screenshot tests

Finally, we use Storybook with Percy for screenshot testing. This presented an interesting challenge. The baseline for Percy screenshots is the last run on master. On pull requests, we only want to evaluate screenshots in packages that have changed, but we must always establish a complete baseline. We briefly entertained the idea of creating a new Percy project for each package, but decided that wasn’t a scalable solution. We decided to use a single Percy project, and run partial builds on feature branches.

To ensure that we generate a complete baseline, all screenshots are generated on the master branch. There’s no manual approval of diffs on master, so we can publish our packages without waiting for Percy to finish.

When we invoke its build-storybook CLI command, Storybook runs our .storybook/config.js file to load stories. We dynamically invoke the Webpack require.context command to load the appropriate stories using the value of STORYBOOK_SOURCE_DIR. Because calls to this Webpack API are meant to be statically analyzable, this was difficult to get working.

Finally, we invoke percy-storybook to upload whichever stories were built to Percy for screenshot testing by comparison against the last baseline.

Dependency Validation

Lerna packages each have their own package.json, which is what allows each component to version independently. Unfortunately, this also means that each package must explicitly specify the other monorepo packages it imports from. If one of its dependencies is not specified, the package will not work when it is installed as a dependency in a web application if the application does not already have a version of that dependency, and it may behave unexpectedly if the application has an incompatible version of the dependency.

To ensure that developers specify all dependencies, we run depcheck in our linting step in CI. If a package imports from any dependency not referenced in the package.json, depcheck will identify this and report a failure. We also wrote a script which developers could run to automatically update the appropriate package.json files to fix any issues that depcheck identifies.

Publishing Updated Package Versions

We publish new releases by running the following commands:

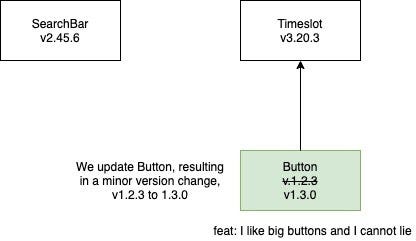

npx lerna version -y --conventional-commit --create-release github

npx lerna publish -y from-packageWe use semantic versioning at Zocdoc. The —-conventional-commits flag causes lerna to analyze commit messages and choose the version increment (major/minor/patch) that seems appropriate.

At this point, lerna has published a new package, whose release version has been incremented based on its current version on the master branch. We now have a working process to publish new packages and ensure that future changes will be versioned correctly. These steps aren’t difficult to learn, but let’s face it — expecting every other developer to remember to do this whenever they make a change, particularly if they’re in a rush or they don’t touch the monorepo often, is probably asking for too much. Our solution was to automate the process.

Automating it sounds great, but lerna version and lerna publish are both interactive, and need user input. You can see we’ve included an argument, -y, which indicates to lerna that it should select the default options for us if we haven’t specified something already, like --conventional-commits.

What we Lerna’d

Multiple Migrations Are Harder Than One

Our legacy design system was inconsistent; it used 3 different frameworks to render screenshots and 2 types of interaction tests. We only added support to the monorepo CI/CD pipeline for one framework for each purpose. As a result, migrating components required us to rewrite many tests.

This strategy had some benefits. Integrating lerna with each testing framework to only run tests affected by changed code was a large effort. Limiting the monorepo to support a minimal set of preferred frameworks helped us quickly complete the setup. Also, individual developers who built new components from scratch in the monorepo did not need to learn several frameworks, and could focus on mastering the few supported tools.

Over time, however, the cost of this choice became clear. Developers who migrated components to the monorepo in preparation for other work found that the migration took much longer than expected. A significant reason for that was our choice to restrict which CI frameworks to support; rewriting tests took much more time than importing git history or updating dependent apps. As a result, we did most of the migration as a dedicated project. Until we could allocate time to complete that, we were in a hybrid state with some components in the old design system and others in the monorepo, which caused significant growing pains.

If you do consider moving to a monorepo, we recommended moving your code over as-is, warts and all. Once in the monorepo, the independent versioning of packages makes it easy to progressively refactor code to remove undesired patterns without blocking the migration effort. If entire components are deprecated, however, the migration is a great opportunity to leave them behind. Our legacy design system had close to 100 independent units of code, and 10–15% had been replaced with better alternatives and were no longer recommended for use. Because we left this code in the legacy design system, developers are less likely to discover or use it now. If we need to use any of this code again someday, we can always migrate it then.

We’re Happy With The Monorepo

After several months of using the monorepo and the legacy design system in parallel, we saw the benefits of the monorepo outweighing its costs, so we committed to a full migration. This has already paid off.

To give an example of where the monorepo really shines, let’s talk about the Zocdoc Video Service (ZVS), which we built earlier this year. The service’s code was split up into a few different webapps; a webapp that handles the provider’s login flow, and webapps that handle the patient’s login flow. ZVS was being built rapidly, and changes were constantly being made. The core logic and many of the components used during the video session needed to be shared between the provider and the patient, so using a shared library made a lot of sense. If we did this using our legacy shared component system, we might have run into a lot of problems, blocking or being blocked by other developers for unrelated changes. The monorepo helped us write the shared code we needed, and we managed to get the service up and running in a few weeks.

“We couldn’t have done ZVS in the time it took us without the help of the monorepo.” — Zack Banton, Team Lead

I hope we’ve shown you that adopting a monorepo for your front-end components can make your developers more productive than a classic component library. However, it is important to note that we’re not done. The monorepo’s drawbacks — such as managing many more package.json files — caused fewer productivity issues than our old design system, but these new drawbacks are still frustrating. We embarked on this project because we saw consistent issues with the way our old system worked, and found that our monorepo could in fact help solve them. Our job now is to look at our new system and try to figure out what can make us more efficient at doing what we love to do — deliver high quality products and features to patients.

About the Authors

Anand Sundaram

Anand Sundaram is a Senior Software Engineer at Zocdoc. When he’s not bringing to life Zocdoc designers’ beautiful visions for improving the experience of booking doctors’ appointments, he’s probably reading nonfiction or playing a real-time strategy video game.

Gil Varod

Gil Varod is a former Principal Front-End Engineer at Zocdoc, meaning somehow there are now only two Gil’s at the company. What a pity.

Tim Chu

Tim Chu is a Senior Software Engineer at Zocdoc. He’s spent most of his tenure working to improve the patient experience, and is currently on rotation with the Android app team, working to improve the patient experience… but on Android!

Zocdoc is hiring! Visit our Careers page for open positions!